From $17K a Year to $60K in 90 Days—Plus an R.E.M. Tribute Playlist

The Monday Blueprint 1.20.25: Essays I've read and last week's market report

Here are some financial resources for wildfire victims.

I have always struggled with budgets.

And heck, if I’m honest, before the ubiquitous of online banking, I struggled balancing my checkbook. It’s not that I wasn’t aware that I couldn’t spend money I promised someone else, it was that I’d look at the recorded numbers in my registry and still not know how much money was in the account. It was just a skill I couldn’t figure until I learned I had (still have) dyscalculia—think dyslexia, only with numbers. Learning this information about myself has made me feel much better about how I move through life. For example, go ahead and ask me when my wife’s birthday is, or my youngest child’s birthday. My own April wedding anniversary I often confuse with my parents’ September anniversary—(this is something, by the way, that I have never confessed out loud to my wife, and turns out she has begun reading all of these newsletters, so sorry honey). Anyway, dyscalculia really messes with remembering dates. I too often forget how old I am. Not being able to balance a checkbook, figure out how a budget works, or forgetting my own family’s birthday has up until very recently made me feel like a horrible human being.

And although my wife forgives me for not knowing her birthday, budgets have been an ongoing battle. For years and years, I’ve said we’ve needed a budget. For years and years, she’s agreed, but then when we sit down to write a budget, we have these massive fights. She sometimes ended the argument in tears. And when I used to smoked, I often ended the argument out on the front porch sucking down a couple of packs of Camel Blues. Yes, I said couple of packs.

Eventually, we separated our checking accounts. Now, every two weeks, because that’s when she gets paid, she puts together a paycheck-to-paycheck budget, but very seldom do we stick to that because we always forget about one bill or another, always end slightly short, forced to catch up the following pay period, except that snowballs into catch up the next pay period after that. There never seems to be a surplus. It’s a never-ending cycle.

We have felt guilt-ridden and as if we have been doing something severely wrong with our money. Why the hell can’t we figure this out?

A paycheck-to-paycheck budget is, however, a legitimate financial system. Each paycheck is carefully allocated to cover essential bills, such as rent or mortgage, utilities, groceries, transportation, and debt payments. Well, often debt payments are the last priority and get too often ignored. Savings, if any, are often small and irregular. Emergency funds are either non-existent or quickly depleted when unplanned costs arise—or even just when planned costs arise.

Traditional solutions for breaking this cycle include tracking every dollar you spend to identify areas to cut back. Actually setting aside a small emergency fund, even if you are only looking at five bucks a paycheck.

A medical emergency could range anywhere from $400 to several thousand. A car repair anywhere between $500 and $1200. A minor home repair can cost anywhere from $300 to $1000. According to the Federal Reserve’s Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households report, 4 in 10 Americans have difficulty covering a $400 emergency expense using cash or its equivalent. That’s not quite half of our population. Financial experts like Dave Ramsey, recommend starting at $1000 for an emergency fund. Others of course suggest you need at least three to six months’ worth of living expenses. Of course, building an emergency fund, they say, is a process, not an overnight task. Uhm, go ahead and do the math on that five bucks a paycheck and at the end of the year you’ve only socked away $130. It’ll take you almost eight years to reach just a thousand dollars.

My personal budget thinking is that we set should aside money now for expenses that are coming down the road. A little bit like the envelope system where you create a list of expense categories (e.g., rent, groceries, transportation, entertainment, etc), and you allocate a specific amount of money to each category based on your budget. When you make a purchase, you remove the money from the relevant envelope, and if the envelope runs out of cash, you just can’t spend anything more in that category until the next budget cycle. If money is left over in an envelope at the end of the budget cycle, it rolls over.

Annual vehicle registration for me is like a hundred-fifty, I think? Making that number up. But if I save $12.50 out of every paycheck, that covers that bill. And from March to March, I don’t have to worry if I have that $150 on me because I’ve incrementally set aside the cash in an envelope. Modern versions of envelope budgeting use apps like Goodbudget, You Need a Budget (YNAB) or EveryDollar.

But. Remember when I said, “There never seems to be a surplus.”

Where the hell is my cash going? What the heck are we doing wrong? Why can’t I manage to set aside thirteen bucks a month for my vehicle registration?

The problem is not the budget. Nor is the problem the five-dollar coffees I have at Breakaway Café—well, they actually cost $2.75 unless you get their Guest Roaster Drip, which is right now Passenger Colombia Divino Nino with tasting notes of cherry, marzipan, and caramel for $3.50. I say five-dollar coffees because of the tip.

My last real estate commission check hit just over $7000. And I was so excited because that week we had actually been able to catch up to all of our regular monthly expenses plus been able to pay off a bit of medical debt, and whole credit card to boot. I had roughly an “extra” $1500 I could set aside for future monthly expenses. Heck, I had the whole whopping $150 vehicle registration early! And then you know what happened? The washer and dryer broke beyond repair.

I knew the washer was going. For months it’d been making a clunking sound with an undercurrent of grinding. Then, one day, the clunking sound stopped, the grinding took over and got very loud, and absolutely nothing happened. We couldn’t even get the thing to fill with water let alone spin. But the machine ran like that for hours before my kid told us that the washing machine was making a weirder noise than usual and was very very very hot to the touch.

I used to rely upon laundromats in my twenties and early thirties. They are a lot more expensive than I remember. At ten dollars per load—and that was just the wash—and we took the wet clothes back home to dry until the dryer up and said, “Wait a minute. Yep, nope I’m done too. It’s been a good run these past twelve years.” So, what, tack on another $20 for drying? Thirty dollars every week for laundry, you’d spend $1560 in a year.

I bought new machines. Thus, no extra cash to set aside.

We could chat about the previous year’s car situation where all three of our vehicles went to the junkyard within weeks of each other. That was when I was still teaching. That’s when I took an entire $7000 real estate commission and stuck it toward a downpayment on a vehicle that now costs me $479 a month between the monthly payment and the auto insurance.

If you have been following me for a while now, you’re aware I used to teach at the university and college levels. This is what my 2023 income looked like:

I made $17,908 teaching.

I made $37,784 selling real estate.

In my first year of teaching at Great Bay Community College, I made even less and needed new glasses. I was told I should consider Medicaid, food stamps, heating assistance—all of that—as a portion of my salary. I walked into the eye doctor to pick up my new glasses, and the optometrist asked how I was able to scam the system so well if I made all of that professor money.

For those of you not in academia, an adjunct is a contract or part-time college professor. Great Bay has around 75% adjuncts. Southern New Hampshire University employs 100% adjuncts. This is typical across the country, not just a New Hampshire issue, and while many schools ar-gue they need to rely upon part-time contingent workers because of low enrollment or budgeting crisis, according to AAUP, “the greatest growth in contingent appointments occurred during times of economic prosperity,” and “the majority of faculty working on contingent appointments do not have professional careers outside of academe…”

Adjuncts don’t just make below poverty level income, we receive zero retirement or health benefits and can lose our jobs at the end point of any semester for any reason or no reason at all. During all this time, my teeth have been slowly rotting due to complications with diabetes—a medical bill that’ll cost $5000 out of pocket to fix. Additionally, the federal government’s student loan forgiveness program for those who work in non-profit organizations doesn’t apply to a single adjunct anywhere because we are considered contract or seasonal employees.

Last year, because of real estate, I was able to visit family in Ohio—something I haven’t been able to do in ten years, I sent my kid to summer camp, and bought that car. In 2024, I brought in $59,780 from real estate alone. This past May, I quit teaching altogether because I made more in real estate than I did in real estate and teaching combined.

This year, 2025, by March, I estimate I’ll have brought in $62,724.25 from real estate—more than $20,900 per month on average. To put that in perspective, that’s three and a half times the $17,921.21 I made teaching for an entire year, achieved in just 90 days. It’s not just a shift in career—it’s a seismic leap in earning potential.

The problem is not your budget.

The problem is you’re not making enough money. Period.

When you are working a traditional 9-to-5 job, your paycheck is essentially carved in stone. My wife has received, over the five years she’s worked at the University of New Hampshire as an administrative assistant with a graduate degree, I believe three cost of living raises.

At Great Bay Community College, with almost ten years of service, I received the same three cost of living raises, and the last two were well-fought through union labor negotiations. Except I didn’t get the benefit of that third raise cause I quit, and the raise would have only bumped me up by a eleven hundred dollars over the course of a year.

Right now, we still need to be careful because we are continuing to play catch up with our old revenue system. The trip to Ohio was a luxury we probably shouldn’t have done. Sending my kid to camp was probably something we shouldn’t have done. When an NYC internship at the American Ballet Company opportunity arose for my oldest daughter, probably something we shouldn’t have done because it drove me gig work at DoorDash. I’m finally getting to the point with our regular household bills where I can create a budget for the real estate business

I’m not saying run out, quit your job, and start a business. It took me three years to quit teaching. But I am saying figure out a way to increase your income.

There’s a pretty good piece over on Culture Study by Anne Helen Petersen on “The Case Against Budget Culture.”

Petersen interviews Dama Miranda on her new book You Don’t Need a Budget. While I haven’t read the book yet, (it’s on my TBR list), Miranda argues that budget culture promotes a rigid, shame-based approach to managing money. The practice she argues is rooted in individualism and restraint, teaches us that financial wellness is about hoarding and strict rules. She says that the budget mindset ignores the systemic realities of inequality and capitalism, framing financial struggles as personal failures.

Our struggles weren’t because we were ‘bad’ with money—they were because our income simply wasn’t enough to keep up with the realities of life. The best budget in the world can’t fix an income problem. If you’re stuck in the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle, it’s not because you’re bad at budgeting, and if you can’t get a raise or a promotion, it’s not because you aren’t good at what you do. The truth is, we’re all working within a system designed to keep us there. But here’s the thing: there are exits—they’re just not clearly marked. If you’re interested in finding one, and you want someone to help you think through your strategy of escape, please reach out.

But the first step is to ditch the guilt. You’re not bad with budgets, and you’re not bad with money. These struggles don’t make you a horrible person—they make you human, navigating a system you never chose and that was never fully explained. Instead of shame, focus on learning the rules of the game and to use every available tool—whether that’s a 9-to-5, a side hustle, Medicaid, food stamps, heating assistance, or even bankruptcy. These aren’t failures. They’re moves on the board, and the only way forward is to stop punishing yourself for playing the game you are stuck with and start strategizing to win.

The Culture Study interview comes on the heels of my new favorite podcast—The Money With Katie Show’s interview with Miranda. If you can get past the beauty tips and the ultrique fashionista, and the episodes are long long, but Katie is a fresh take on a subject that is often overshadowed by the exuberance of finance bros.

Obviously, Miranda is doing the whole book launch tour thing. All hype for the book. 😊But there you go.

IN NO PARTICULAR ORDER

Essays I’ve Read

How the biggest rock band in the world disappeared by Will Leitch

Will Leitch’s essay on R.E.M.’s quiet exit from the spotlight reads like a manifesto against our relentless grind for relevance. The band’s decision to walk away and resist cashing in feels almost rebellious—a declaration: We were here. We mattered. Now, we’ll let you figure the rest out. It’s a powerful counterpoint to a culture obsessed wth clinging to the past, which ties neatly to the MAGA slogan—a call to drag the past into the present without asking if the past fits or even belongs.

Some years ago, Dan Brown gave a talk at the Portsmouth Music Hall in Portsmouth, and the house was completely packed. When Dan opened the presentation for audience questions, the first question was wondering when the hell Dan was going to bring back the pie pan he had borrowed.

Leitch too captures the human scale of greatness by juxtaposing R.E.M.’s exit with a more intimate moment: drummer Bill Berry at a grocery store. Such stories remind us that legends, whether global rock icons or bestselling authors, are just people. And it’s in those unpolished, human moments that we see the antidote to the myth of greatness.

Smith argues that economists should read Marx as a cautionary tale of how sweeping ideologies can distort reality when applied recklessly to governance. Smith’s essay was inspired by Alex Moskowitz’s bombastic critique that economics is “fake” for ignoring figures like Marx. While Moskowitz’s oversimplification is fair to critique, Smith reduces the humanities to simple ideological and/or political critique.

Humanities scholars aren’t simply spinning ideological tales or launching unfounded critiques though. They’re engaging in a deep interrogation of how knowledge is constructed, how power dynamics shape discourse, and how systems, including economic ones, affect human lives.

Economics, whether anyone wants to admit to it or not, sits right in that liminal space, using math and models to try and capture the squishy, unpredictable nature of human behavior. It’s not pure science, and it’s not pure art; it’s a hybrid, which is why it so often feels simultaneously profound and limited.

Both Smith and Moskowitze miss the potential nuanced interplay between disciplines, where the rigor of one can be enriched by the critical frameworks of the other.

But mainly, I just enjoyed the essay because I like watching people fight online.

This essay is a Trojan horse. Scanlon’s not really about TikTok, but about something much bigger: the erosion of our shared narratives.

Think about how stories used to anchor us:

Nationally, there were Walter Cronkite’s broadcasts or blockbuster movies that everyone watched.

Locally, it was town halls, coffee shop conversations, and regional newspapers.

Now? It's fractured. Everyone’s siloed into their niche—watching, scrolling, or listening to entirely different things.

We’re still speaking, but no longer understanding. This fragmentation reinforces tribalism and makes the world feel less human. Instead of the shared stories that help us empathize with each other, we get algorithms feeding us stories designed to provoke or affirm, never to connect.

TikTok and other platforms are a paradox: they document our cultural shifts but in ways that are fleeting, ephemeral. There’s no permanence, no anchor to history. Who will archive the stories told in TikTok trends? The viral moments that shape culture? Platforms aren’t built for preservation—they’re built for profit.

The lawsuit against the Internet Archive underlines this tension between cultural preservation and corporate ownership.

Without shared stories, we don’t just lose connection; we lose a cohesive sense of what it means to be human, and this fragmentation undermines democracy itself. Without a shared narrative, we can’t act collectively—whether that’s to preserve the online digitized culture, respond to climate change, or even agree on basic truths.

Lavery’s essay is a beautifully verbose love letter to the art of being concise.

I used to drive around in a little blue, beat-up Chevette in the early 90s until my brother wrecked it. He managed to ram into a building or a tree—something that shouldn’t have been hard to miss, but he hit it dead-on like he was aiming for it.

Me and a bunch of other nerds—though they had way cooler cars than mine—decided I should get an alarm for the Chevette. Instead of the usual WEE-oo WEE-oo WEE-oo, we thought it’d be hilarious to program the alarm to say, in a super whiny voice, “Get away from me, you’re making me nervous.” And if someone actually stole the car—the alarm wouldn’t turn off. But in the same whiny voice, “Does your mom know you’re doing this?”

Lavery’s longwindedness is, of course, a part of the joke. He knows he’s breaking his own rule as he writes, and that self-awareness makes the whole thing land perfectly. It’s not just advice; it’s advice wrapped in a performance, a sly wink to the reader that says, “Yeah, I could’ve kept this short, but then you wouldn’t be having this much fun.”

I’m not trying to be grand or impressive here, but instead revel in our own moments of smallness. If Lavery’s perfectly fine blurb could talk by the way, it’dsound like my Chevette alarm: deeply unimpressed, slightly whiny, and offering enough personality to stick in your head.

LAST WEEK IN THE STOCK MARKET:

Are We Finally Winning the Inflation Fight?

The U.S. markets wrapped up one of their strongest stretches in months. The S&P 500 climbed 1.00%, the Dow Jones rose 0.78%, and the Nasdaq led the way with a robust 1.51% gain. Meanwhile, the Russell 2000 added 0.40%, reflecting modest optimism in smaller-cap stocks. These moves came as investors cheered improving inflation data and a slightly cooler economic outlook.

The rally came against a backdrop of falling bond yields and an easing in fears of aggressive Federal Reserve action. While the markets celebrated, commodities told a more cautious story—crude oil dropped 0.81%, settling at $78.04, while gold slid 0.40%, reflecting a shift away from safe-haven assets.

Big Themes to Watch:

Cooling Inflation Brings Market Cheer

The latest inflation data offered a glimmer of hope for weary investors. While the Cleveland Fed’s Hammack warned that the battle against inflation isn’t over, signs of progress spurred optimism. Core inflation remains sticky, but easing headline numbers have markets hoping the Federal Reserve will hold rates steady—at least for now. The labor market, however, remains a wild card. Continued strength could reignite concerns about wage-driven inflation, keeping the Fed’s hands tied when it comes to rate cuts.

Tech Stocks Regain Momentum

Tech led the charge last week, with the Nasdaq outperforming its peers. Investors remain bullish on the sector’s long-term potential, particularly in AI and cloud computing. However, the industry isn’t without challenges, as profit-taking remains a concern, and analysts caution against premature excitement. Still, the Nasdaq’s strength suggests investors are betting on a tech-driven recovery later this year.

Commodities Signal Mixed Sentiment

Crude oil’s dip reflects shifting demand expectations, while gold’s slight decline points to a more risk-on market environment. These moves come as investors weigh improving equity performance against long-term uncertainties like global growth and geopolitical risks. The takeaway? While optimism is creeping back into equities, commodities remain an anchor for those hedging against potential volatility.

Looking Ahead

As we move further into 2025, two key stories loom large: TikTok's future and the Los Angeles wildfires.

Speculation surrounding a potential TikTok ban continues to stir up the tech sector, with companies like Meta and YouTube poised to capitalize on the app’s uncertain future. Speculation swirls around Trump’s evolving stance on TikTok, with indications he may reverse his prior hardline position. If the app gets the green light, this would mark a surprising pivot from his previous administration’s crackdown. And maybe the green light already happened over the weekend, or rather at least a barely yellow?

All of this has reignited debates about national security, data privacy, and the ripple effects on tech giants. If the platform faces significant restrictions, it could reshape the digital advertising landscape and open doors for U.S.-based rivals.

And you can read my own take on the whole TikTok ban if you are so inclined:

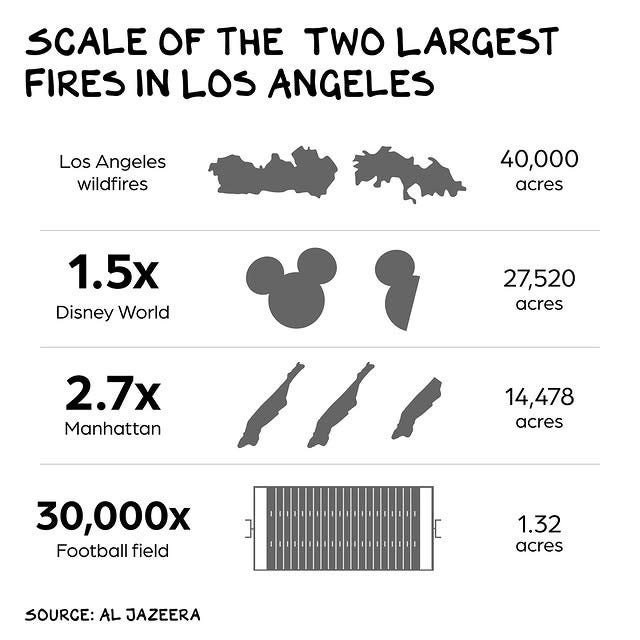

Meanwhile, the Los Angeles wildfires are creating local economic strain but are unlikely to significantly impact the national economy, according to economists. Uhm, have you seen this graphic from No Mercy / No Malice at profgalloway.com?

Galloway writes, “The LA fires will likely go down as the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.”

You can read Galloway’s entire take here: https://www.profgalloway.com/after-the-fires/

Steve Ponders the World

Rethinking the Economics of the Everyday

As I worked through last week’s stock market report, one line gave me pause: “The labor market, however, remains a wild card. Continued strength could reignite concerns about wage-driven inflation, keeping the Fed’s hands tied when it comes to rate cuts.” It made me wonder—does this idea of wage-driven inflation still hold up in a globalized, tech-driven economy?

This question led me down a rabbit hole of labor dynamics, gig work, and the shifting relationship between wages and prices. The result is my latest piece, “The $80 Coffee Economy: Wage Myths in a Globalized World.” Steve Ponders the World is a new feature I’m trying out in Coffee with Steve family of newsletters, where I’ll explore big economic questions in a way that’s personal, thoughtful, and (hopefully) a little fun. It might evolve over time, but for now, consider this the beginning of something intriguing.

Subscribers can check it out now on Substack. Not a subscriber yet? Join me for a deeper dive into the economics of the everyday.

The $80 Coffee and Wage Myths in a Globalized World

Here are some financial resources for wildfire victims.

Question of the Week

How much of a finance bro do you think I am? On like a scale of 1 to 10. Or choose your own guage!

And looking ahead, next week on the Monday Blueprint, watch for the post “We Blew Through $7K in Two Weeks: Learning to Manage Success”