A Desperate Attempt to Wrest Control Over Her Own Body

Steve Ponders the World: Rethinking the Stories We Live By and Everything We Think We Know

The push to control trans bodies is not a cultural anomaly but a continuation of a long-standing playbook: strip away rights, criminalize survival, and force the most vulnerable into underground economies just to access basic care. The New York Times editorial condemning Trump’s anti-trans policies is critiqued for its passivity—acknowledging injustice but offering no real call to action, mirroring how institutions have historically wrung their hands while legitimizing the very debates that led to these crises.

The United States has a long history of systemic oppression that we don't like copping to. But I don't want to compare here Trump to Hitler—that deep gut level reaction externalizes our darkest parts—pretends that fascism, genocide, racial supremacy are foreign imports, when in reality, the U.S. helped mix that Kool-Aid1.

The one thing Trumpians don't get about the liberal democrat arm of the U.S.: we are just as patriotic, just as pro-America. And the one thing the Coastal Elite don't get about the conservative republican arm of the U.S.: y'all aren't a bunch of dumb hick rednecks driving around in oversize pick-up trucks with ball sacks hanging from the back and sporting a big giant American flag.

That fantasy—whether it's the Fox News 'Murica crowd or the MSNBC latte-sipping resistance2—is a curated identity as much as anything else. Both sides have been fed a carefully packaged, highly marketable version of what it means to be conservative or liberal, and a whole lot of people live inside those myths, sometimes without even realizing it.

The idea of a new golden age3 has always been part of American mythology.

Trump's slogan “Make America Great Again” isn't even original thought—Reagan used it, Clinton used it. I personally don't believe that America's greatness comes from some misplaced nostalgia from the single-family house boom of the '40s and '50s, the white picket fence, the washer and dryer in every home, the rise of the two-car family, the tendency towards pull yourself up by your own bootstraps4 isolationism or even the nation's rise to global economic superpower. Like every other country on this planet, just like all people groups, we have committed atrocities and evil. Yet, we have just as many moonshots, and we yearn and work and strive for better5.

Which brings us to The New York Times editorial board's recent piece “Trump's Shameful Campaign Against Transgender Americans6.” The editorial gets a lot right—it correctly identifies Trump's executive orders as a deliberate, targeted attack on an already vulnerable minority. The piece even draws historical parallels to past U.S. Government-sanctioned oppression, noting that history doesn't look kindly on these kinds of policies.

But the piece conveniently sidesteps their own responsibility in admitting that the New York Times echoed, amplified, and gave legitimacy to the conditions that made Trump's culture war crusade possible, mirroring the anxieties and hesitations of what was already present in American society—wringing hands over “both sides” of trans rights debates while lending editorial pages to op-eds that questioned whether trans people were pushing too hard, too fast.

Had it not been The New York Times, it was someone else—some other respectable institution giving airtime to the idea that maybe we should slow down on this whole “letting trans people exist in public spaces” thing7.” But wait has almost always meant never, and moderation is the maintenance of the status quo.

The NYT’s closing line “...Americans would do well to remember the hard-won lessons of our history” assumes that the lessons are self-evident—that we, as a collective, remember the lessons. But the American public has a habit of burying, forgetting, and rewriting history into comfortable narratives—the kind that make us the good guys.

Here in New Hampshire, House Bill 283 seeks to remove from public schools, among other topics, history, holocaust, and genocide education. Looking back at my own educational journey, for example, I remember Uncle Tom's Cabin. I think this was junior year American history with Mr. R.—a man who's own personal history as a Viet Nam vet haunted the classroom.

The school sat directly beneath the flight path of Neil Armstrong Airport, a small rural airstrip about nine miles from Wapakoneta and a short drive from the Armstrong Air & Space Museum—not far from where Neil himself grew up. The airport primarily serves corporate, recreational, and private flights. My brother-in-law works on Crown International’s planes there to this day; the company's headquarters just a few miles away in Minster, Ohio—a town where, in the 1930s, farmers gleefully carved out runways in their cornfields to make it easier for WWII Germans to invade8. But what I remember most about that airport was the crop dusting and Mr. R. occasionally spilling his coffee and throwing his glazed donout across the room as he ducked underneath his desk when a plane flew just a bit too low because in that moment all he could think about was his Viet Nam tour. Suffice to say, we skipped over that entire chapter of Viet Nam in our American history textbook.

We did, however, learn about Harriet Beecher Stowe's and her novel. To be clear, we did not actually read Uncle Tom's Cabin. Both our textbook and Mr. R gave the book lip-service, and we were told why the book was important, that the narrative was a vital component to ending slavery. Though we were taught and tested over the apocryphal meeting between Stowe and Lincoln, when Lincoln said, “So, you're the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war,” I mean, what a great story, a great mythologizing of American history9.

I never got around to reading Uncle Tom's Cabin until much later as an adult. And as an adult I learned first and foremost the book is a bored white-washed read. Written by a white woman for a white audience, the novel positioned slavery as a moral dilemma that good white people could help solve—an approach that made it palatable to its intended readership. Additionally, the book framed enslaved women as passive victims in need of white saviors, centering white abolitionists rather than Black resistance. Yes, the book is anti-slavery but is also drenched in the “good” Black person vs. “bad” Black person. By the time the Civil Rights Movement rolled around, the novel had been canonized as a major anti-slavery text, despite its paternalistic framing and its sidelining of Black agency.

All of that you probably know. But what the U.S. long-sanitized educational system chooses not introduce you to is Harriet Jacobs, author of The Incidents of the Life of a Slave Girl.

Incidents, by the way, is memoir. And when Jacobs was working on her manuscript, she approached Stowe for publishing support. Stowe dismissed Jacobs’ and offered to write her version Uncle Tom's Cabin, Essentially, a rewriting of personal history for mainstream America.

Harriet Jacobs was born enslaved in North Carolina. Her enslaver, Dr. Norcom (renamed “Dr. Flint” in her memoir), made it clear early on that she wasn’t just property—he saw her as his to take. He sexually harassed her from the time she was a teenager, whispering threats and promises, making it clear that if she didn’t submit, he could and would make her life hell.

Jacobs' writes,

My master, Dr. Flint, had his perfidious purposes, and I was doomed to perpetual jealousy and fear. He told me I was his property; that I must be subject to his will in all things... The influences of slavery had had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.

And:

When he (Flint) told me that I was made for his use, made to obey his will in all things, he was touching a deep chord of resentment, and the thought that I had no power to control the impulses of my own soul!

In a desperate attempt to wrest control over her own body, she took a white lover, Samuel Sawyer, and had two children. If she had to be with a white man, she thought, at least this one wasn’t her enslaver. At least this might protect her children.

Norcom was enraged. He threatened to take her children away as punishment. So, Jacobs hid. She crawled into a tiny attic crawlspace in her grandmother’s house, nine feet long, seven feet wide, and three feet high. She couldn’t stand. Her body atrophied. Her muscles wasted away. She developed nerve damage that lasted the rest of her life. She trained herself to be motionless. The only light from a small peephole she drilled in the wall to see her children playing outside.

Norcom kept hunting her. He put ads in newspapers. Sent bounty hunters. Searched the North, the South, everywhere. He wanted her back not just to enslave her, but to break her.

She remained in the attic crawlspace for seven years, a detail that never made it into Uncle Tom's Cabin.

When Jacobs finally escaped to the North, she still wasn't free, spending the next decade evading capture, dodging laws like the Fugitive Slave Act, constantly afraid. It took another ten years for her to secure legal freedom.

We like to think we’ve moved past our worst histories, but the ghosts of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl tell us otherwise. Dr. Flint chased Harriet Jacobs across states, spending himself into financial ruin, just to try and force a woman back under his control. He never succeeded. But financially and emotionally he destroyed himself trying. That same pathology, the need to dominate, the refusal to let go of control, echoes in every new wave of backlash against those seeking freedom.

We had so many questions when Mr. R. jumped underneath his desk. We did not understand what was going on and were not only concerned for Mr. R.'s well-being, but genuinely scared. The hush over the classroom after we could no longer hear the sound of the plane, Mr. R emerging from the desk with newly-coffee stained shirt... He never said a word about what had just happened or why. He only wrung his hand from the coffee and continued teaching. The trauma of individuals made the Vietnam chapter uncomfortable; the trauma of an entire nation makes certain chapters at the least inconvenient: fugitive slave laws, the Indian Removal Act, Pace vs. Alabama, Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Dawes Act, Racial Integrity Act, Buck vs. Bell, Mississippi Appendectomies, the California Eugenics Laws, Executive Order 9066, Korematsu vs. United States, Puerto Rican Sterilization Campaign, Jim Crow Laws, the Termination Policy, Loving vs. Virginia, the Comstock laws, Griswold vs. Connecticut, Eisenstadt vs. Baird, Relf vs. Weinberger, sterilization of Indigenous women, Bowers vs. Hardwick, Don't Ask Don't Tell, Lawrence vs. Texas, Roe vs. Wade, Operation Wetback, Dobbs vs. Jackson Women's Health Organization, various Bathroom bills, anti-drag and public performance laws, and gender-affirming care bans.

The parallels between gender-affirming care bans and past government restrictions on bodily autonomy is an astounding long and gut-wrenching history. The history is also the history of people finding ways around. Harriet Jacobs hid in an attic for seven years to avoid being raped by her enslaver.

With legal access to trans-health-care becoming more and more restricted, people turn to informal, and often dangerous, alternatives. Hormones smuggled in from Chile, Peru, Santo Domingo, Mexico, where they can be purchased for $500 and a $50 plane ticket, once back in the United State are often flipped for $5000. Injection parties feature not not even backroom clinics but living rooms, dining rooms, some doctor from somewhere performing breast implants and other body modifications, sometimes successfully; other times, the consequences are deadly similar to 1960s coat hangar abortions10.

This is what happens when the government decides that some people’s bodies don’t deserve care. When hospitals and insurance companies are pressured to deny treatment. When legal access is yanked away, forcing people to make impossible choices. It’s a communal survival network built out of necessity, not choice. I want you to know that the system isn’t broken—it’s working exactly as intended. By forcing trans people out of legitimate medical spaces, bans create a thriving underground market where access depends not on safety, but on who you know and how much you can pay. And like every system designed to control who gets care and who doesn’t, the most vulnerable suffer the worst consequences.

Once the government successfully strips away rights from one group, it moves to the next the next group. The tactics don’t change—just the targets. The Fugitive Slave Act turned ordinary citizens into slave catchers and judges were literally paid more if they ruled in favor of the endeavors11. The Chinese Exclusion Act set the legal precedent for targeting and excluding entire racial groups, later paving the way for Japanese Internment12. The Racial Integrity Act banned interracial marriage and gave teeth to eugenics programs. The Red Scare was a cover for purging LGBTQ+ people from government jobs. The Lavender Scare fired thousands of employees from government jobs for just the suspicion of being queer13. The War on Drugs criminalized Black communities, locking up generations under mandatory minimum sentencing, while opioid addiction in white communities later got framed as a health crisis. The Patriot Act normalized mass surveillance and indefinite detention without trial14. Every single time, there were people who thought, 'This doesn't affect me. This isn't my fight.' Until, suddenly, it was.

The New York Times opinion piece, “Trump’s Shameful Campaign Against Transgender Americans,” ends on a vague, moralizing note rather than any real, meaningful call to action. The Times takes a familiar, high-minded approach—condemning Trump, providing historical context, but ultimately letting the reader off the hook. It’s sympathetic without being urgent, aware without being activist. Which is exactly how you end up with a world where the same institution that once platformed “both sides” debates on trans rights now writes unnamed authorial editorials lamenting the consequences.

Before the Civil War, human ownership wasn’t a crime. It was a business model, and for centuries, U.S. law didn’t just allow slavery—it codified, protected, and enforced it. And we should also never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was legal.

WHAT YOU CAN DO RIGHT NOW:

Donate to a trans healthcare fund.

Call or email your legislators.

Amplify trans voices.

Educate yourself + push back on misinformation.

Not just “helped.” We were basically the head bartender. Hitler and the Nazis literally referenced American eugenics laws, Jim Crow policies, and Native American displacement as inspiration for their own racial purity projects. (See: James Q. Whitman's Hitler's American Model.)

I do like a good latte-sipping. Or diner coffee that tastes slightly burnt but still somehow perfect. Which is to say: personal taste is not a political statement, but we've managed to make it one.

I was super impressed with Trump's inaugural address but the man is not an allusion-heavy thinker, and my guess is most of his executive orders were pre-written by the Heritage Foundation (I didn't research this. I'm just assuming. But tell me I'm wrong.) And I feel like I can pick out Trump's authentically produced executive orders, like the banning of paper straws and a move back toward plastic straws, which is really IMHO the least of anyone's worries on either side of the political fence. Probably, the inaugural address was written by Stephen Miller, steeped in reactionary narratives and particularly obsessed with nostalgic nationalism and likely drawn from Reagan's speeches, far-right European nationalist rhetoric, and the Lost Cause myth. Anyway, props to Stephen Miller for a banger speech. (See: Max Greenwood, Miller and Bannon Wrote Trump Inaugural Address, Report. Also: See: Trump posts on X, Feb. 7—"I will be signing an Executive Order next week ending ridiculous Biden push for Paper Straws, which don't work. BACK TO PLASTIC." )

Pull Yourself Up By Your Bootstraps. The first known usage was 1834 in The Adventures of Baron Münchhausen, which many years later they made a movie. If you haven't read the story (or seen the movie) this is a satirical German story about an absurdly exaggerated adventurer. One tale features the Baron pulling himself and his horse out of a swamp by his own hair. We saw this sentence about the same time in a newspaper, “To attempt to raise oneself over a fence by the straps of one's boot.” By the late 1800s, the phrase became a way to mock people who preached radical self-reliance. Newspapers (the Internet of the day) memed the phrase to criticize people who thought the poor could magically become wealthy without structural help. The Workingman's Advocate wrote in 1867, “One who thought he could lift himself by his own bootstraps, as the saying goes, has been pretty effectually undeceived.” By the 1920s 1930s, the phrase began to shift as the American self-made man myths were taking off. Herbert Hoover pushed the idea that people could bootstrap themselves out of poverty through rugged individualism—uhm, that guy was famous for depression era Hoovervilles, I do believe.

A lot of people have been fighting for better while others have actively pushed things backward. America's “progress” is a constant war between competing visions, and if you don't see that, you're probably the guy yelling at your HOA because your neighbor put up a Pride flag. Or a giant Vote Trump sign even though the election is over.

The Times, in its usual high-minded but conveniently late to the party fashion, has suddenly decided that Trump's full-frontal assault on trans rights is bad. This is the same newspaper that not even a year ago platformed think pieces agonizing over whether trans people might be asking for too much and whether we should all just calmly debate their right to exist over lox and bagels Sunday brunch.

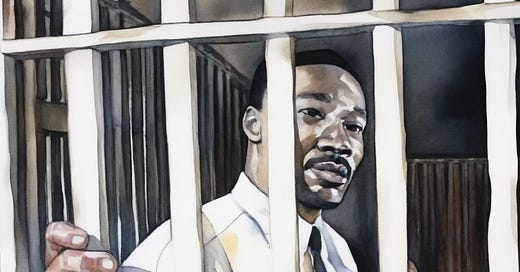

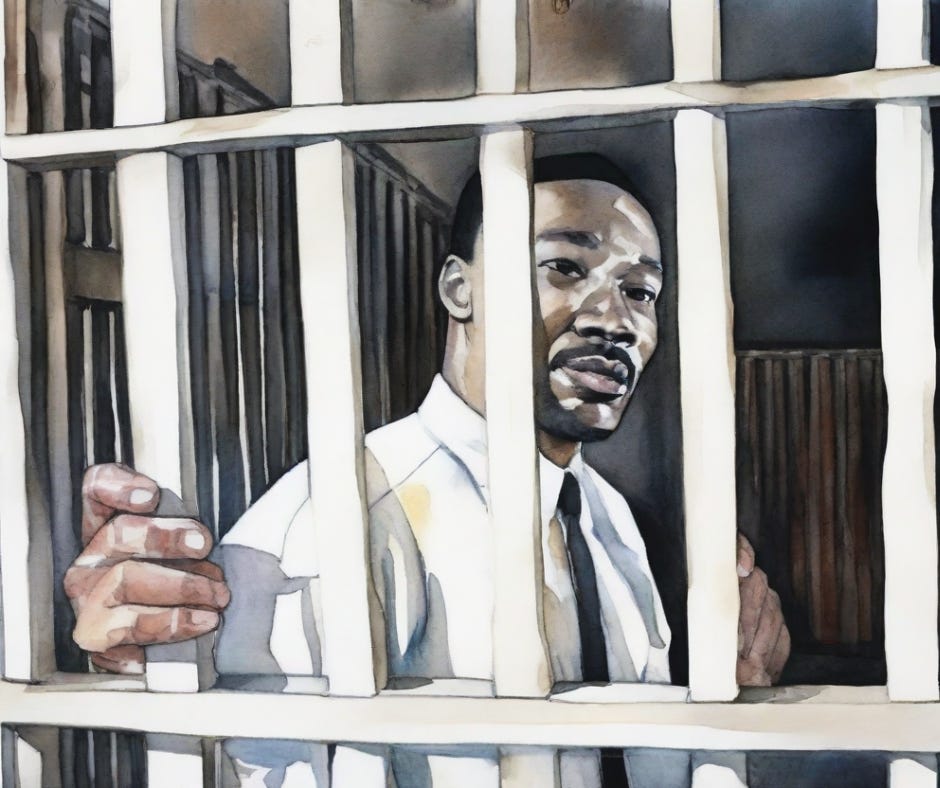

See: For example, Johnathan Cahit, Moderation Is Not the Same Thing as Surrender, The Atlantic Nov 27, 2024. Ugh, “Moderation is not the same as surrender” is one of those phrases that sounds reasonable but, when you poke, turns out to be an ideological smokescreen—the kind of rhetoric that allows people to doing nothing while they pretend to be thoughtful instead of just complicit. There is no moderate position on whether trans people should have equal rights—either they do, or they don't. This is the same logic used to delay the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, marriage equality, and literally every major social justice movement. It's how institutions delay action. Moderation frames trans rights as something to be negotiated, rather than basic human dignity. Bonus points if you find the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr quotes in the essay.

That whole part of Ohio, of course, was deeply German—Minster, New Bremen, Maria Stein, all those little towns with their brick churches and strong Catholic roots still had close ties to Germany in the 1930s. And if you dig into U.S. History, there was a good amount of pro-German sentiment before the war. Henry Ford blatantly printed antisemitic newspapers, and the German American Bund held regular rallies at Madison Square Garden. And growing up, my favorite restaurant meal was a breaded pork tenderloin sandwich with dill pickles at Adolph's, which was akin to walking into a bar called Mussolini's and ordering a Negroni.

This is classic American myth-making: we love neat, cinematic moments where history turns on a single interaction. In reality, Lincoln was more influenced by political, military, and economic pressures than any one novel, no matter how influential. Stowe’s book played a role in shaping public opinion, but war happens because of power, not paperback bestsellers. And other examples abound. Paul Revere was not a lone rider but April 18, 1775 saw at least a dozen riders including William Dawes and Samuel Prescott and most of them were drunk—except Revere, who was stodgy anyway. The Boston Tea Party was more a passive-aggressive tax protest than a moment of unhinged rebellion. Oh yea, we owned that tea by the way, it did not belong to the British and the biggest “damage” was to a broken lock (which later paid for by the protesters—because decorum matters, I guess). And probably the biggest myth-bust: the first Thanksgiving in 162 was a military negotiation between the Wampanoag and the Plymouth settlers because the Wampanoag were in a bad spot ravaged by disease and outnumbered by rival tribes, and they saw the Pilgrims as potential allies—and more importantly, a source of European weapons. Also, probably no turkey, which I know is just wrong.

See: Vice TV, Black Market Hormone Replacement Therapy. This isn’t exactly a CVS pickup. The underground hormone market runs on the same principles as any other prohibition-era economy: scarcity, desperation, and middlemen who know how to work the system. That $5,000 is like a 900% markup—because when people are desperate, someone will always find a way to profit. Also See: bootleggers, snake oil salesmen, the American healthcare system.)

If a judge ruled that a captured Black person was ‘actually’ an escaped slave? Ten bucks in his pocket. Adjusted for inflation, that’s the equivalent of “We’ll Venmo you $350 if you hand over this human being to a bounty hunter.”

Fun fact: at least 2,000 of those interned were children. America has always been enthusiastic about caging kids.

Because nothing says ‘danger to democracy’ like two women in sensible loafers owning a cat together.

See: Guantanamo Bay, NSA wiretaps, and every single ‘random’ TSA search that somehow always picks the same demographic.